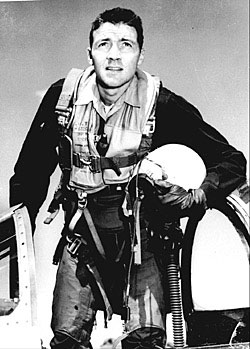

Colonel John Boyd (public domain photo)

This is the text of a speech I delivered at the Gartner Group Security and Risk Management Summit in June 2015. I originally wrote the speech for Sir Roger Carr, the Chairman of BAE Systems, to use at one of his public appearances. But it was too good not to re-use for myself as the BAE Applied Intelligence’ strategy lead. I felt no shame in doing so, seeing that I’d written it…

Introduction

Good afternoon. Thank you for coming. It is a privilege to speak with you today. I’ve been asked to speak to you about digital crime: its rise, its significance, and what can be done about it.

But I also know that I am the last thing between you and beer, so I will keep this talk as short and sweet as I can.

Certainly, “cyber security” (I hate that phrase, but there we are) is a topic that can be treated lightly, and it is ambitious to try and cover the whole subject in 20 minutes. Nonetheless. I will discuss the rise of digital crime: how criminal enterprises, state-sponsored actors, and other parties are robbing the industrialized world of its secrets and personal information. I’ll discuss the impact that these activities have on businesses, citizens and governments. And I’ll discuss what can be done from our perspective as BAE Systems, one of the world’s largest defense contractors and providers of digital crime solutions.

Introduce Self

But first, allow me to introduce myself and BAE Systems.

I am the strategy officer for BAE Systems Applied Intelligence. I’m a recovering analyst; you might know me from, as they say on late-night TV, “another network,” in this case Forrester, where I covered data security and mobile security, and advised hundreds of enterprise clients on these topics, and on security strategy. I also wrote a fairly well-regarded book on security metrics called, funnily enough, “Security Metrics.”

Introduce BAE

Most of you probably know BAE Systems because of the work we do with the UK government and the Ministry of Defense. BAE’s role is to safeguard and enhance our customers’ vital interests. We have a robust defense business: we build aircraft such as the the Typhoon; we build, service and repair naval ships; we make land-based armaments, such as the Bradley Fighting Vehicle; and we are a key supplier to aerospace and defense companies worldwide.

Most of you probably do not know that we have a billion-dollar risk and security business, which we call Applied Intelligence. We are probably the largest cyber-security company that you have never heard of. We have over 5,000 customers in many industries in three continents, with a concentration in financial services. We secure our customers’ intellectual property and their email; we detect fraud and reduce the cost of compliance; we help them identify and reduce their financial and reputational risks; we host their key collaboration services; and we monitor and defend their networks from intrusions.

All of these activities give us a unique vantage point on the challenges of cyber-security, and on the problem of digital crime.

The Rise of Digital Crime

First, let’s talk about the rise of digital crime: what it is, and what it means. When we speak about “digital crime” we mean the use of computers either as the main component of, or as an accessory to, criminal activities that result in financial gain or in competitive advantage. Broadly speaking, “digital crime” includes all dastardly deeds that span cyber-crime, financial crime, fraud, and insider activity. The common element is that unlike purely physical crimes — for example, pickpockets on a crowded subway car, these crimes rely on technology in some way.

Increasingly, we see significant interplay between the different types of digital crime. Cyber is a key enabler of financial fraud, of healthcare fraud, and of the theft of industrial secrets. As reported by Scotland Yard in April 2014, seven out of ten financial fraud offenses involve cyber in some way. And because every part of society is becoming increasingly automated, instrumented, and network-connected, we expect that cyber will be involved in an increasingly large proportion of crimes over the next few years.

Two types of threat actors: nation-states and criminal enterprises

Today, digital crime is perpetrated by two main types of actors: nation-states and criminal enterprises. Many of the most important cyber incidents that you have no doubt read about over the last five years have involved nation-states. These nation-states are engaged in state-sponsored hacking and industrial espionage on a grand scale. Two years ago, for example, US forensics firm Mandiant revealed that an elite hacking unit of the People’s Liberation Army was responsible for stealing industrial secrets from the U.S. defense industrial base, leading security software firms, and other businesses. More recently, North Korea stands accused of penetrating the networks of Sony Pictures to embarrass executives and steal intellectual property.

The goal of these types of state-sponsored cyber activities is to obtain industrial secrets for sovereign advantage. The adversaries are advanced, persistent, and most certainly a threat.

Criminal enterprises present a danger of a different sort. Their goals are to obtain what one might call “toxic data”: payment card details; personal health information; and personally identifying information, such as pension and other government identifiers. This information is fungible, and can be sold on black markets for profit, or to commit identity theft — at which point it is used for fraudulent financial purposes.

Some examples. Last year, the U.S. retailer Target suffered from a data breach that caused the payment card details of over 40 million customers to be stolen, plus the personal details of over 70 million additional customers. And last month, the healthcare company Anthem was breached, exposing millions of healthcare records. A Bloomberg report suggested that the real target of the Anthem breach were the employees of its customers, which included Northrop Grumman and Boeing. Attackers were in effect using weaknesses found in Anthem’s defenses to get to these other companies.

The advantages attackers have over defenders

Although both classes of attacker — state-sponsored actors and organized criminal enterprises — have different objectives, they have several things in common, which give them advantages over their targets, who must defend themselves:

- First, both classes of adversary are supported by an integrated criminal supply chain. The supply chain is fully stratified, with loose networks of cyber weapons suppliers, middle-men, intermediaries, distributors, and 24 x 7 support providers. The wheels of this supply chain are helpfully greased by digital currencies such as BitCoin, which enable the anonymous exchange of funds between buyers and sellers.

- Second: both classes of adversary are highly creative, willing to use all means at their disposal. These means include hacking, lying, fraud, identity theft, infiltration, and compromising trusted suppliers. They also include the use of any and all channels: phone, cyber, wi-fi, in-person and physical.

- Third: both depend on the fact that their victims’ networks are increasingly far-flung, cloud based, and porous. With the advent of mobile, cloud, social networking, consumerization, and extended digital supply chains, companies must deal with exponentially more complexity in their networks than they did just ten years ago.

But it gets worse. You may not know that that the lingua franca of the Internet, the TCP and IP protocols, were never designed to be secure. They were designed to make the Internet resilient, to allow packets to flow to their destinations even when parts of the infrastructure were damaged. Every security protocol we have, was written — after the fact — to flow on top of those resilient, but insecure, protocols. Because security was never woven into the basic building blocks of the Internet, attackers inevitably find flaws in the ones we’ve fitted on top of them.

Against such a backdrop, the adversary is always assured of asymmetric advantage. Defenders have to get it right all the time. Attackers, just once. To use a colloquial phrase, one might expect that for attackers, this should be rather like shooting fish in a barrel. And indeed it has been.

The Impact of Digital Crime

The impact of digital crime is significant no matter how one chooses to measure it.

- The cost of digital crime begins with the direct costs; the cost of cleanup, notifications to customers, and fines. Target stores has spent almost $150 million cleaning up after their data breach. Heartland Payments Systems, a payment processor, was breached in 2008 and had over a hundred million payment card details stolen, with direct costs from the breach totaling nearly $150 million, only 30 million of which was covered by insurance. In general, industry analysts estimate that breaches of customer information can cost victims — companies and customers — millions of dollars. But the criminals nearly always make a mint: the gangs that broke into Target, for example, may have made over 675 million dollars of profit.

- The cost of digital crime includes the damage to the victim’s reputation. A significant breach can cause significant personal embarrassment to executives and to customers. The co-chairman of Sony Pictures, for example, was forced resign last month because her company’s security was so poor. The CEO of Target stores resigned because of its hack. Security is indeed becoming a board level issue in the sense that people are getting fired because they don’t have enough of it.

- The cost of digital crime includes changes in stock price and profits in the wake of a security breach, although these are usually temporary. Often overlooked are the inevitable class-action lawsuits that arise against public companies after data breaches. The management of Heartland Payment Systems has spent over five years defending itself against 27 separate consumer and institutional class-action lawsuits.

- Finally, the cost of digital crime includes the loss of trust of one’s customers. Once lost, it is often difficult to regain. This is particularly challenging with firms that sell to other businesses. In the Heartland case, after years of growing its merchant base at double-digit rates between 10 and 20 percent, in the 2 years following the breach, merchant growth went into reverse, dropping 2%.

(more examples here…)

These costs — direct costs, damage to reputation, stock price and profit drops, lawsuits, and loss of trust — are significant costs for any individual organization to bear. Taken in aggregate, the near-continuous stream of bad news leads to a gradual erosion of trust in digital business in general.

What can be done

The problems associated with digital crime are complex. So are the solutions, but that is in part because of the way we as customers, suppliers and national governments have been thinking about the problem of digital crime. We need to think differently. We need to think deeply. And we need to think quickly.

Systems thinking, not silo thinking

First, we need to think about systems as a whole, and not about silos.

To use an analogy, consider the West’s responses to various failed and successful hijacks of aircraft by terrorists. The first plots were revealed in 2006. A plot was foiled to detonate liquid explosives on 7 airplanes over the Atlantic. These explosives were peroxide-based and easily disguised in drinks bottles. After foiling the plot, the US and UK airline authorities duly banned bringing liquids through airport security. In September 2001, the 9/11 hijackers took control of airline cockpits using knives and box-cutters. Authorities duly prohibited knives and box-cutters on flights. Then, in December, show-bomber Richard Reid tried to set off a PETN-based bomb embedded in his shoe; the plot was foiled. Authorities duly forced passengers to remove their shoes.

Security expert Bruce Schneier argues that none of these things have made any difference in minimizing the risk of hijackings. Only two things have: reinforcement of cockpit doors, and the fact that passengers are willing to fight back against attackers.

Whether you agree with Bruce or not on this point, you can surely agree that the pattern used for preventing hijackings is “silo thinking”: looking for the artifacts used in the last attack and hoping that strategy will be effective in preventing the next one. Enumerating the things that are bad, rather than spotting the patterns that are bad.

In cyber, we have been following a similar script. Consider the case of Target stores. Target suffered a horrendous breach; most people can appreciate the seriousness of that. What is less appreciated is that Target was compliant with the industry standard for security at the time of the hack: the Payment Card Industry’s Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS). By definition, Target owned and operated:

- anti-virus software

- firewalls

- intrusion detection systems, and:

- log management software to filter through security device logs.

All of these items are mandated by PCI-DSS and are required to be installed on systems that process cardholder data.

In addition, the retailer also operated a security operations center in Minnesota. It had installed a $1.5 million advanced malware detection system, FireEye, which did detect the malware that ultimately compromised its network.

In short, Target could not possibly have been accused of skimping on security.

What happened? Target’s failure came down to something fairly simple: the various silos of security did not talk to each other. Target’s advanced malware detection system saw the malware and created an alert. But the information was not acted on by Target’s staff. It was lost amidst the noise, or not presented in a relevant or timely way. Target did not arrive at the conclusions they needed to fast enough, which was not “you’ve got malware” but: “your point of sale systems are being taken over by a criminal enterprise.” In short, Target’s tragedy was the failure to think of its data sources, individual security systems, directories, suppliers and point-of-sale terminals as a single, interconnected system, and to attach relevance and meaning to the patterns of behavior seen within it.

A system, in the broad definition, is a set of connected technologies or processes that form a greater, more complex whole. Target thought it had a system in place, but it’s clear it only had silos: FireEye, the Bangalore team, the Security Operation Center in Minnesota, and many individual security technologies. When needed the most, they acted (or didn’t act) separately.

When we rethink security, we must re-imagine security processes as an integrated whole. Systems thinking. To prevent and detect attacks, one must integrate all the elements — email, networks, physical, web, monitoring systems and many others. The components don’t all have to be from the same company, but they need to be integrated in such a way that the data flows seamlessly. Crucially, the information needs to be filtered and packaged so that it can be rapidly assessed, evaluated and acted on by human analysts.

Getting the full picture of risk

Second, we need to think about the full picture of risk.

Digital crime, particularly cyber crime, does not happen in a vacuum. Regardless of whether an attacker is trying to steal secrets, purloin personal information or launder lucre, nearly every type of digital crime can be reduced to a few common steps.

- The attacker must plan his “campaign”: perform reconnaissance, communicate with confederates, collect insider information, create exploits, or infiltrate a network of people.

- The attacker must commit his crime: break into a system, steal an identity, launch a denial of service attack, abuse administrator privileges, or use non-public information.

- The attacker must harvest his gains: purchase or sell goods, make fraudulent claims, sell secrets, or launder money.

Every method used in these steps generate some sort of tell-tale signal or artifact: a phone call, an entry in a log, a transaction, an intrusion alert, a payment or a sale.

Appreciating the full picture of risk means having full knowledge, within the span of your control, of all of these artifacts. It means having the ability to sift through noise to find signal. It means acquiring, analyzing and acting on information at high speeds and at large scales. And it means having effective processes, technology and skills to spot anomalies, communicate them coherently, and act quickly.

Scaling up

Third, we need to scale up.

The problems of digital crime are complex, critical and costly. I will explain this by way of example. Much of the work that we are inspired to do by our customers are multi-billion-pound problems, for example:

- First-party financial fraud costs institutions $18 billion a year globally

- Intellectual property stolen from U.S. firms costs $300 billion every year

- U.S. health care fraud costs insurers and the government nearly $75 billion annually, of which over $6 billion is cyber-related

- Tax fraud globally is estimated at 5% of the total global economy: over $300 billion in the US and over $100 billion here in the UK

What unites these problems is that they are sufficiently large to escape the grasp of any one company, institution, or government. Effective approaches must necessarily be multi-company, industry-wide, and transnational in scope. For complex, critical and costly problems, only large-scale solutions will suffice.

For example, here in the UK, we work with the Insurance Fraud Bureau. Software supplied by our Applied Intelligence unit analyzes every auto and property insurance claim submitted by every claimant in the country. This industry-wide capability has resulted in over 600 arrests and a large reduction in the amount of insurance fraud committed. This is not something that could work for a single insurer. This truly is a Big Data problem.

Here in the United States, we are working with several state insurance agencies to reduce medical insurance fraud, again, as an industry-wide solution within each state. We provide essential network security services for nearly 15% of all American banking and credit union institutions. We monitor a quarter-million daily transactions processed by a New York-based clearing house, about $1.2 billion worth of instruments every day.

These are all examples of how having a multi-company, transnational vantage helps solve industry-wide problems.

Conclusions

The three strategies I’ve described — employing systems thinking, not silo thinking; getting the full picture of risk; and “scaling up” to span industries and international boundaries — are key to solving the complex, costly and critical problem of digital crime. But these items will not be sufficient in and of themselves. Because what we also need as businesses, as consumers and as society as a whole is a new mindset.

The risk intelligence mindset

The mindset we need to adopt is a more informed, intelligent approach to thinking about and managing risk: “risk intelligence” if you like. Not every plan to protect the business will be perfect. It is impossible to imagine a world in which there is no fraud, no theft, and no successful cyber-attacks. BAE might well wish it could sell silver bullets in addition to the conventional kind, but silver bullets do not exist.

What I mean by “risk intelligence” is that customers have enough information to act, even in conditions of uncertainty. I mean that when customers’ most well-considered security and risk plans fail, they can still act decisively, and can make decisions appropriate for their businesses. Customers need to be able to:

- quickly acquire data about risks and threats at the highest level that could affect them and their customers;

- effectively analyze the data on hand to create information that can be put to use; and then:

- decisively act on that information to achieve better business outcomes: for example, reducing fraud, repelling cyber attacks, or rapidly responding to a break-in.

Learning from John Boyd

There is a precedent for this type of thinking, and it comes courtesy of BAE’s main business, the military business. In the 1970s American military strategist Colonel John Boyd wrote about something called the “OODA loop,” which stands for Observe, Orient, Decide and Act. Boyd theorized that in combat conditions, one must:

- Observe the enemy’s movements;

- Orient oneself by creating a mental picture of the situation;

- Decide on the courses of action available, and then:

- Act decisively

Boyd believed that the combatant who can observe, orient, decide and act fastest would win the battle. This means achieving the clearest and most accurate conception of battlefield position, and then taking action, as fast as possible. Boyd also believed that a combatant who can observe, orient, decide and act faster can overwhelm his adversary’s decision-making capability, achieving victory in a fraction of the time required by conventional warfare.

That was why Hitler’s blitzkrieg attacks were so effective. It is why the US-led Operation Desert Storm, for which Boyd was a key architect, was able to conquer Iraq — a country whose territory is nearly twice the size of the UK — in less than four days.

It is also why digital crimes take days, months and years to detect. Adversaries are able to observe, orient, decide and act much more quickly than their victims.

So, when we say that to properly combat digital crime, we need “risk intelligence,” we mean quickly acquiring data, effectively analyzing it, and decisively acting. In essence: speeding up customers’ own analytics and decision-making processes to match or exceed the speed of the adversary.

Result: make customers’ jobs easier

Imagine a world where risk intelligence becomes the norm. Done right, our customers’ jobs become simpler. Today, the Chief Information Security Officer’s role in most organizations is to catalog all of the vulnerabilities in the environment; prioritize them; and then serially eliminate them one after the other. He or she buys many best-of-breed products to solve many narrow problems. Along the way, he or she writes policies that few people read, and some business unit owners actually regard as harmful. He or she spends valuable staff time answering hundreds of pesky audit questionnaires. That is the day job.

The after-hours job is what happens when the company is actually compromised or subjected to fraud or attack. In these circumstances, the Security Officer scrambles, dodges, and weaves before making the best of a bad situation. Because policy is prioritized over speed of decision-making, the Security Officer is always caught by surprise.

In future, the Chief Information Security Officer’s job will be measured not by the pound — that is, by the weight of policies produced and purchase orders placed. It will be measured instead by the tick — that is, by the number of ticks of the clock between when the adversary initially acts, and when he or she is able to acquire, analyze and act in response, or in advance of the adversary’s next move.

Parting thought

I will close with a quote from Sir Winston Churchill:

“Want of foresight, unwillingness to act when action would be simple and effective, lack of clear thinking, confusion of counsel until the emergency comes, until self-preservation strikes its jarring gong - these are the features which constitute the endless repetition of history.” Let us learn from history.

Thank you for your time and attention today.