Risk Management is Where the Confusion Is

Lately I’ve been accumulating a lot of slideware from security companies advertising their wares. In just about every deck the purveyor bandies about the term “risk management,” and offers their definition of what that is. In most cases, their definition does not match mine.

I first encountered the term “risk management” used in the context of security in 1998, when I read Dan Geer’s landmark essay Risk Management is Where the Money Is. At the time, I was completely gobsmacked by its thoughtfulness and rhetorical force. It was like a thunderbolt of lucidity; several days later, I could still smell the ozone. Seven years later, I’ve found that much of his essay stands up well. Unfortunately for Dan’s employer at the time, purveyors of bonded identities did not flourish and monetize electronic commerce security as he had predicted. But he was absolutely correct in identifying digital security risk as a commodity that could be identified, rated, mitigated, traded, and above all, quantified and valued.

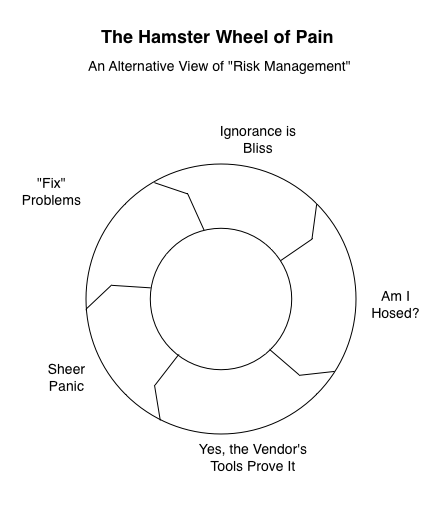

Most of the decks I see miss this last point. Nearly everyone shows up with a doughnut-shaped “risk management” chart whose arrows rotate clockwise in a continuous loop. Why clockwise? I have no idea, but they are always this way. The chart almost always contains variations of these four phases:

- Assessment (or “Detection”)

- Reporting

- Prioritization

- Mitigation

Of course, the product or service in question is invariably the catalytic agent that facilitates this process. Follow these four process steps using our product, and presto! you’ve got risk management. From the vendor’s point of view, the doughnut chart is great. It provides a rationale for getting customers to keep doing said process, over and over, thereby remitting maintenance monies for each trip around the wheel. I can see why these diagrams are so popular. Unfortunately, from the perspective of the buyer the circular nature of the diagram implies something rather unpleasant: lather, rinse, repeat—but without ever getting clean. (I’ve been collecting these charts, by the way. Soon, I hope to be able to collect enough to redeem them for a Pokemon game.)

Here’s the cynical version of the “risk management” doughnut, which I call the “Hamster Wheel of Pain”:

- Use product, and discover you’re screwed

- Panic

- Twitch uncomfortably in front of boss

- Fix the bare minimum (but in a vigorous, showy way). Hope problems go away

The fundamental problem with the Hamster Wheel model is simple; it captures the easy part of the risk management message (identification and fixing things) but misses the important ones (quantification and triage based on value). Identifying risk is easy because that is what highly specialized, domain-specific diagnostic security tools are supposed to do. They find holes in websites, gaps in virus or network management coverage, and shortcomings in user passwords. Quantifying and valuing risk is much harder, because diagnostic tool results are devoid of organizational context. To put this simply, for most vendors, “risk management” really means “risk identification,” followed by a frenzied process of fixing and re-identification.

That’s not good enough, if you believe (as I do) that risk management means quantification and valuation. If we were serious about quantifying risk, we’d talk about more than just the “numerator” (identified issues). We’d take a hard look at the denominator: that is, the assets the issues apply to. Specifically, we would ask questions like:

- What is the value of the individual information assets residing on workstations, server, and mobile devices? What is the value in aggregate?

- How much value is circulating through the firm right now?

- How much is entering or leaving? What is its velocity and direction?

- Where are my most valuable (and/or confidential) assets? Who supplies (and demands) the most information assets?

- Are my security controls enforcing or promoting the information behaviors we want? (Sensitive assets should stay at rest; controlled assets should circulate as quickly as possible to the right parties; public assets should flow freely)

- What is the value at risk today—what could we lose if the “1% chance” scenario comes true? What could we lose tomorrow?

- How much does each control in my security portfolio cost?

- How will my risk change if I re-weight my security portfolio?

- How do my objective measures of assets, controls, flow and portfolio allocation compare with others’ in my peer group?

These aren’t easy questions. Pete Lindstrom’s earlier post to this list on asset valuation (and the ensuing thread) highlighted how difficult achieving consensus on just one of these questions can be. I don’t claim to have any of the answers either, although some of the folks I’ve invited to be on this list have (and are) taking a shot at it. What I do know is that none of the commercial solutions I’ve seen (so far) are even thinking about these things in these terms. Instead, it’s the same old hamster wheel. You’re screwed; we fix it; 30 days later, you’re screwed again. Patch, pray, repeat. The security console sez you’ve got 34,012 ”security violations” (whatever those are). And uh, sorry to bother you, but we’ve got 33 potential porn surfers in the Finance department.

We’re so far away from real risk management that it’s not even funny, and I’m wondering if it’s even worth the effort in the short term.

Is it time to administer last rites to ”risk management”? I think it is. This is not as controversial a statement as it might sound. For example, risk management is often confused with risk modeling—an entirely different but vital part of security analysis. Risk modeling research helps us understand how security works (or doesn’t). Research from folks on this list, (Geer, Soo Hoo, Kadrich, Shostack, Lindstrom, Eschelbeck) and others continues to astound and amaze me. Economists we need; what we don’t need are traveling salesmen bearing Wheels of Pain.

My point is that ”risk management” as an overarching theme for understanding digital security has outlived its usefulness. Commercial entities abuse the definition of the term, and nobody has a handle on the asset valuation part of the equation.

Key Indicators Supplant Risk Management

If “risk management” isn’t the answer, what is?

Even though he was not the first to say it, Bruce Schneier said it best when he stated that “security is a process.” Surely he is right about this. But if it is a process, exactly what sort of process is it? I would submit to you that the hamster wheel is not what he (or Dan) had it mind. Here’s the dirty little secret about “process”: process is boring, routine, and institutional. Process doesn’t always get headlines in the trade rags. In short, process is operational. How are processes measured? Through metrics (numbers about numbers) and key indicators (consistently-measured health diagnostics).

In mature, process-driven industries, just about everyone with more than a few years tenure makes it their business to know what the key barometers of the firm are. Take supply chain, for example. If you are running a warehouse, you are renting real estate that costs money. To make money you need to minimize the percentage of costs spent on that real estate. The best way to do that is to increase the flow of goods through the warehouse; this spreads the fixed cost of the warehouse over the higher numbers of commodities. Unsurprisingly, the folks running warehouses have a metric they use to measure warehouse efficiency. It is called “inventory turns”; that is, the average number of times the complete inventory rotates (turns) through the warehouse on a yearly basis. When I was at FedEx in the mid-90s, the national average for inventory turns was about 10-12 per year for manufacturers. But averages are just that; all bell curves have tails. The pathetic end of the curve included companies like WebVan, who forgot they were really in the real estate business and left one of the largest dot-com craters as a result. No density = low flow-through = low turns = death. Dell occupies the high end: back in 1996, their warehouses did 40 turns a year. 40! Dell’s profitability flows directly from their inventory management and supply chain excellence; Kevin Rollins surely eyes this number like a hawk.

I use this (simple) example only because it illustrates how a relatively simple key indicator speaks volumes about company operations. It isn’t the only number warehouse operators watch, but it is one of the most important. Supply chain operators also tend to look at freight cost per mile, percentage of “empty” (non-revenue generating) truck miles, putaway and pick times, and distribution of “A”/“B”/“C” velocity SKUs, among others.

Several themes emerge from the supply chain key indicators list. First of all, every example in the list incorporates measures of time or money—and since time multiplied by labor costs yields money, it’s fair to say that they all ultimately reduce to monetary measures. Second, all of the indicators are well-understood across industries and consistently measured. That means they lend themselves to benchmarking, in the sense that a high-priced management consultancy could go to a wide variety of firms, gather comparable statistics, gain useful analytical insights, and make a buck on the analysis. Third, although the numbers themselves may not always be straightforward to calculate, they can nonetheless be gathered in an automated way.

I think this is where we need to go next. What I want to see nowadays from vendors or service providers is not just another hamster wheel—what I want is a set of key indicators that tells customers how healthy their security operations are, on a stand-alone basis and with respect to peers. Barbering on about “risk management” just misses the point, as does fobbing off measurement as a mere “reporting” concern. If solution providers believed that particular metrics were truly important, they would benchmark them across their client bases. But they don’t; every vendor I’ve posed this idea to looks at me like I have two heads. (Gerhard’s firm might be the lone exception, bless him.)

My short list of (mildly belligerent) vendor questions, therefore, includes these:

- What metrics does your product or service provide?

- Which would be considered “key indicators”?

- How do you use these indicators to demonstrate improvement to customers?

- Could you, or a management consultant, go to different companies and gather comparable statistics?

- Do you benchmark your customer base using these key indicators?

I want to see somebody smack these out of the ballyard, but somehow I think I’ll be waiting a while.

Time to get off the Hamster Wheel of Pain; next up, key indicators.

I could go on, but you get the idea. Comments and spirited ripostes are welcome as always. And if you are part of (or know) an organization that is doing this well, I want to hear about it, off the record of course.